A recent study of over 80,000 Europeans concluded that speaking more than one language is associated with delayed aging. Further analysis suggested that the protective effect of speaking one foreign language diminished with age, while the protective effect of speaking two or more foreign languages was more robust with aging [1].

Beyond communication

Learning a foreign language and maintaining this knowledge in the long term is not an easy endeavor. However, as research suggests, it can bring benefits that go beyond simply communication and cultural enrichment.

Research on multilingualism (“the regular use of more than one language”) suggests that it has a protective role in delaying cognitive decline and age-associated neurodegenerative diseases. [2-4]. However, those studies have some caveats, such as investigating people with cognitive decline rather than healthy people or having small sample sizes.

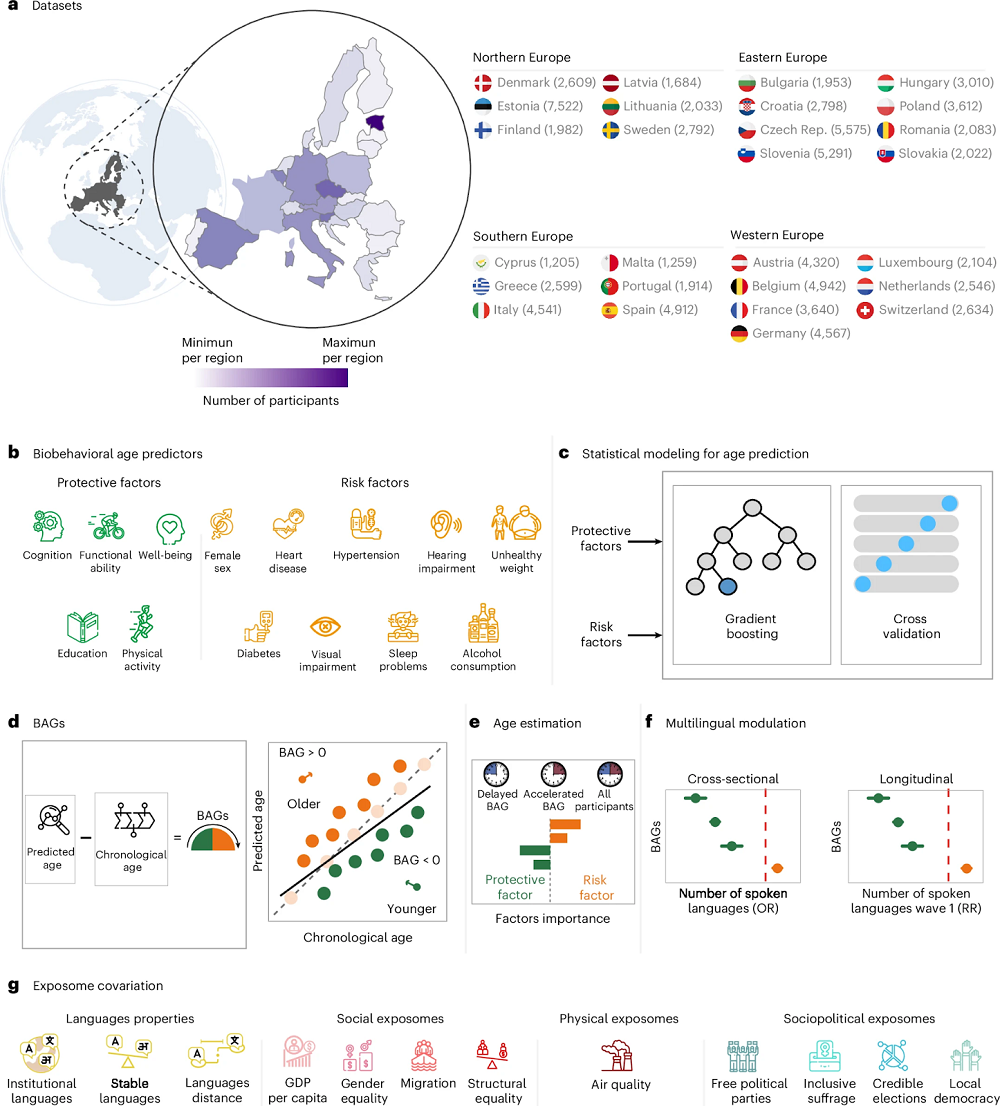

In a recent study, researchers sought to address these shortcomings and investigate whether multilingualism influences aging. They utilized data from a large population of 86,149 individuals with a mean age of 66.55 years (age range: 51-90 years) from 27 European countries, excluding people with a diagnosis of dementia.

In this analysis, multilingualism was assessed as an aggregate, country-level percentage of people speaking one, two, three, or more languages. At the same time, individual data was used to estimate the aging rate.

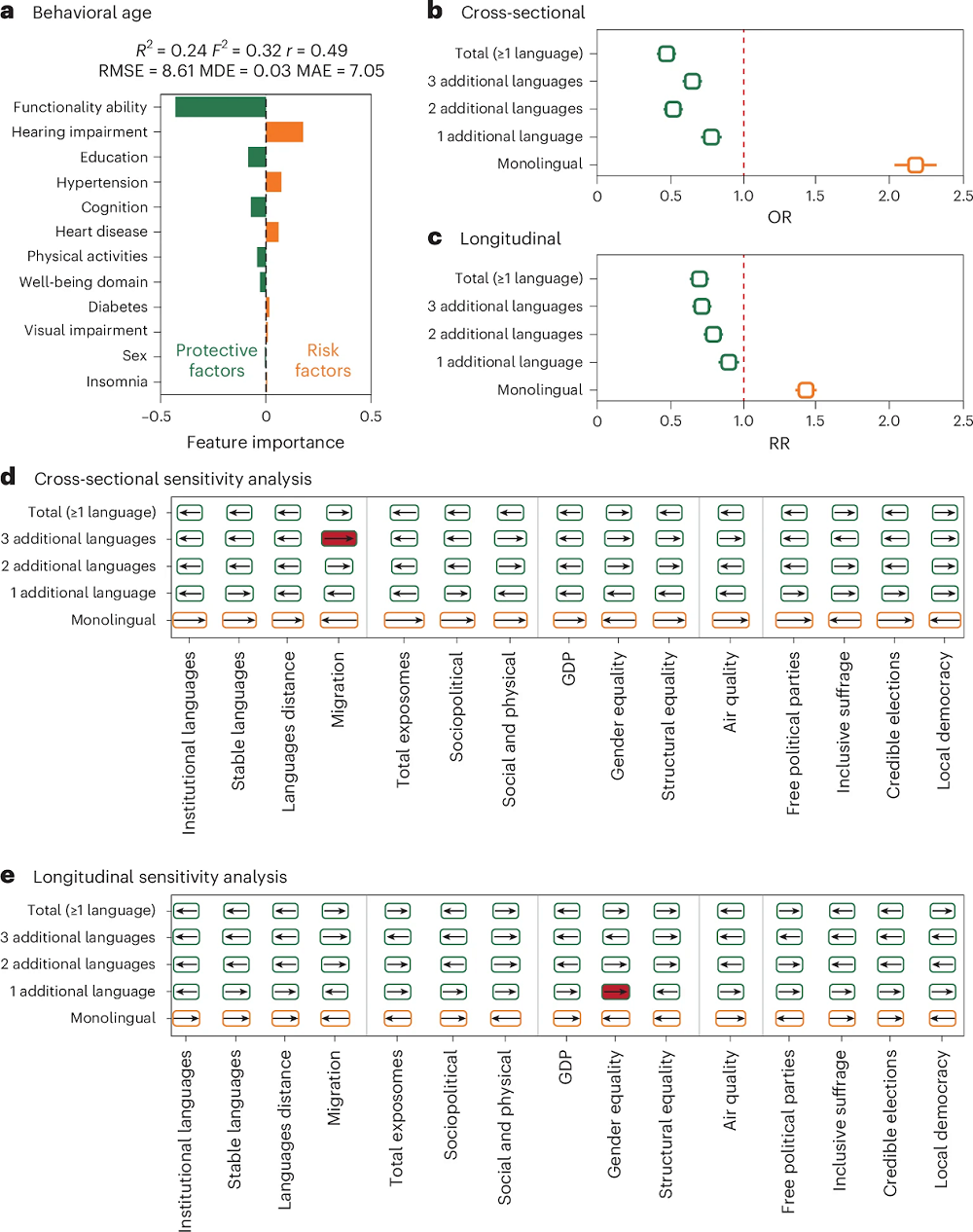

The authors measured this rate by calculating biobehavioral age gaps (BAGs), which represent the difference between an individual’s chronological age and the age predicted by a model. This measure is more sensitive than the indirect markers used in previous studies on this topic. The model that calculates BAG considers both positive and adverse risk factors to which the individual was exposed. Positive BAG values indicate accelerated aging, while negative values suggest delayed aging.

The more the merrier

The researchers performed two types of analysis: cross-sectional analysis, which analyzes data at a single time point, and longitudinal analysis, which allows for the analysis of a population over a period of time. While the results differed slightly, they both point to multilingualism having positive effects.

According to the cross-sectional analysis, people who speak only one language (monolinguals) are 2.11 times more likely to experience accelerated aging. In comparison, people who speak at least one more language are 2.17 times less likely to experience accelerated aging. The exact odds differ depending on the number of languages spoken, with bilinguals 1.3 times less likely to experience accelerated aging, trilinguals 1.96 times less likely, and polyglots who speak four or more languages 1.56 times less likely.

Analyzing this population over time through longitudinal analysis suggests a similar protective effect of language learning, with monolinguals having 1.4 times higher chances of experiencing accelerated aging over time, while the risk is 1.43 times lower for multilinguals, and as previously depends on the number of languages spoken and showing a dose-dependent effect. The results of this analysis showed that bilinguals were 1.11 times less likely to develop accelerated aging, trilinguals 1.25 times, and polyglots speaking four or more languages 1.41 times less likely.

An additional analysis that grouped participants by age suggested the same protective effects. However, it also indicated that the protective effect of speaking one foreign language diminished with age. In contrast, the protective effect of speaking two or more foreign languages remained more robust with aging.

Other factors

The authors of this study noted that many previous studies did not account for confounding factors and exposure to various lifestyle-related and socioeconomic factors, which can all lead to inconsistent results and improper data interpretation. To correct that, they used aggregate country-level data to adjust their analysis for different linguistic, physical, social, and sociopolitical conditions. They observed only minor changes in the magnitude of the protective effect of multilingualism.

They only noted the effects of two factors. The positive impact of delayed aging in polyglots was lost in the cross-sectional analysis following adjustments for immigration status, and in the longitudinal analysis, a positive effect in the bilingual population was lost when the researchers controlled for gender equality.

The authors speculate that since migration is often linked to different stressors, it “can lead to stressful multilingualism,” where acquisition of other languages is done out of necessity and pressure. Such stress and pressure might diminish the positive effect of language learning. However, as the authors discuss, their analysis is lacking a significant amount of data regarding migration, such as whether it was forced or voluntary, the length of stay, migration history, and other relevant details. Therefore, this result should be interpreted with caution.

Their results also suggest that similar negative factors, as in the case of migration, can be present in environments lacking gender equality, thereby contributing to the limited positive effects of multilingualism for people in those environments, suggesting that factors beyond individual lifestyle choices might have a profound impact on aging.

Not the first evidence, but strong evidence

Overall, this study revealed a strong association between multilingualism and a reduced risk of accelerated aging, whereas monolingualism was associated with an increased risk of accelerated aging.

While this study was not the first to show the positive effects of speaking multiple languages, it addressed many shortcomings of previous studies, thereby strengthening the evidence and adding additional support that multilingualism, along with other lifestyle factors, can be incorporated into public health guidelines as a protective factor against accelerated aging.

Although this study draws conclusions from a robust dataset, it cannot establish causality between the observed associations. Further studies, based on experimental or intervention-based designs, are needed to establish causality.

The researchers also point out that their “measures were coarse, and participants likely represented mixed multilingual profiles.” Still, the strength of the observed associations suggests that the observations can be generalized, as they are derived from the broad variability of profiles. However, to identify differences in the level of protection between various multilingual profiles, there is a need for additional studies that incorporate individual-level multilingual metrics such as age of acquisition and proficiency level, as this analysis relied on country-level data, which limited the authors’ conclusions and ability to analyze the impact of those individual factors on aging trajectories.

Literature

[1] Amoruso, L., Hernandez, H., Santamaria-Garcia, H., Moguilner, S., Legaz, A., Prado, P., Cuadros, J., Gonzalez, L., Gonzalez-Gomez, R., Migeot, J., Coronel-Oliveros, C., Cruzat, J., Carreiras, M., Medel, V., Maito, M. A., Duran-Aniotz, C., Tagliazucchi, E., Baez, S., García, A. M., & Ibanez, A. (2025). Multilingualism protects against accelerated aging in cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses of 27 European countries. Nature aging, 10.1038/s43587-025-01000-2. Advance online publication.

[2] Alladi, S., Bak, T. H., Duggirala, V., Surampudi, B., Shailaja, M., Shukla, A. K., Chaudhuri, J. R., & Kaul, S. (2013). Bilingualism delays age at onset of dementia, independent of education and immigration status. Neurology, 81(22), 1938–1944.

[3] Craik, F. I., Bialystok, E., & Freedman, M. (2010). Delaying the onset of Alzheimer disease: bilingualism as a form of cognitive reserve. Neurology, 75(19), 1726–1729.

[4] Venugopal, A., Paplikar, A., Varghese, F. A., Thanissery, N., Ballal, D., Hoskeri, R. M., Shekar, R., Bhaskarapillai, B., Arshad, F., Purushothaman, V. V., Anniappan, A. B., Rao, G. N., & Alladi, S. (2024). Protective effect of bilingualism on aging, MCI, and dementia: A community-based study. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 20(4), 2620–2631.

View the article at lifespan.io