In a new study, the amino acid arginine shows promise in animal models of amyloid aggregation due to its ability to promote protein folding. The researchers suggest that it could be useful for early prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s [1].

Hold it and fold it

Amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, can be potent bioactive molecules in their own right. Arginine, an amino acid abundant in foods like pumpkin and meat, has been shown to act as a chaperone, a molecule that assists in protein folding, [2] and is already used to treat several diseases. In this study, published in Neurochemistry International, researchers from Kindai University in Japan and partner institutions attempted to use this quality of arginine to tackle Alzheimer’s disease.

While scientists still don’t fully understand the etiology of Alzheimer’s, protein misfolding definitely plays a big role [3]. Misfolded amyloid beta (Aβ) protein forms fibrils and then plaques, which are Alzheimer’s most iconic hallmark, although the role of soluble Aβ may be even greater. Chaperones can sometimes inhibit misfolding of aggregation-prone proteins [4].

Preventing fibril formation

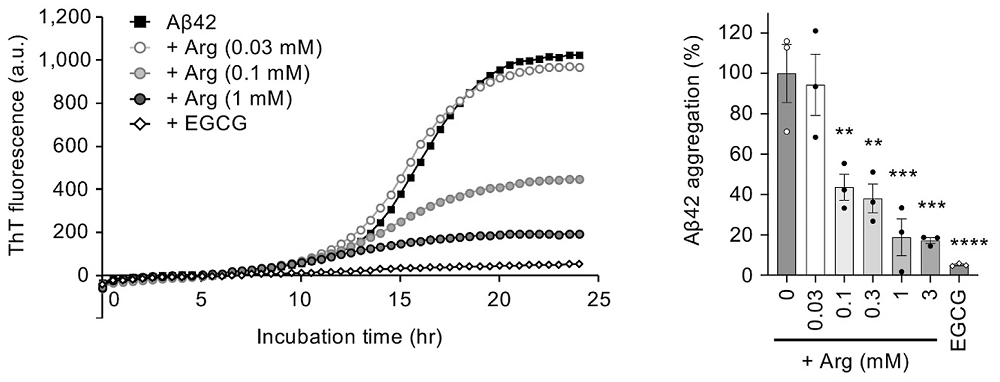

First, the researchers incubated synthetic Aβ42 peptide (the 42-amino acid form of amyloid-beta that is especially prone to aggregation) and monitored aggregation in vitro. As a positive control, they used epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a green tea polyphenol known to prevent amyloid aggregation [5].

Adding arginine reduced the fibril formation signal in a concentration-dependent way, up to roughly 80% inhibition at 1 mM arginine. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) showed shorter, less developed fibrils.

Interestingly, EGCG, a ‘gold-standard’ amyloid inhibitor in vitro, was more potent than arginine. The authors, however, did not take EGCG into their fly or mouse experiments, possibly because its profile is already well explored and less drug-like: EGCG has poor oral bioavailability, binds promiscuously to many proteins, is slow to cross the blood-brain barrier, and has shown liver toxicity at therapeutic doses.

Fruit flies with human Aβ

The researchers then experimented with drosophila flies genetically modified to express human Aβ42 in the eye (a standard neurodegeneration model). Arginine reduced the fraction of cells with Aβ aggregates in a dose-dependent manner. The authors reported no change in Aβ transgene expression, meaning that arginine affected aggregation/clearance, not production. Aβ toxicity, which in this model, manifests in eye shrinkage, was reduced as well.

“Our study demonstrates that arginine can suppress Aβ aggregation both in vitro and in vivo,” explaind Prof. Yoshitaka Nagai, a senior author. “What makes this finding exciting is that arginine is already known to be clinically safe and inexpensive, making it a highly promising candidate for repositioning as a therapeutic option for AD.”

Fewer dense plaques in mice

Finally, the researchers moved to a mouse model, which carries three amyloid precursor protein (APP) mutations and is used to mimic Aβ42 plaque deposition starting around 3-4 months. These mice also develop behavioral abnormalities.

Mice received 6% arginine in drinking water starting at 5 weeks of age. This translates to a human equivalent of 940 mg/kg/day, about twice the maximum oral arginine dose currently approved in Japan for urea cycle disorders.

At 6 months (mid-stage), immunohistochemistry for Aβ showed a clear reduction in plaque area and number in the cortex and hippocampus compared to controls. However, at 9 months (near saturation of plaque load), the effect was weaker, with only a nonsignificant trend toward reduced plaque area in the hippocampus, likely because deposition was already near the ceiling. Notably, arginine-treated mice had fewer dense-core plaques than controls at both 6 and 9 months.

Insoluble Aβ42 was significantly reduced by arginine at 6 months, while soluble Aβ42 was unchanged. Like with the flies, App mRNA expression was unchanged, again arguing for an aggregation/clearance effect rather than changes in APP production.

The researchers then tested the mice’s cognitive abilities. In the Y-maze test, which assesses memory and anxiety via spontaneous alternation and locomotor activity, arginine significantly improved results at 9 months. At 6 months, however, only a weak trend toward improvement was observed, which somewhat contradicts the Aβ accumulation results.

Variability between individual mice was high, which the authors note as a possible reason for inconsistent behavioral results. However, it is also possible that the level of dense plaques, which was lower at 9 months than at 6 months, played a decisive role.

Aβ42 accumulation drives neuroinflammation, so the researchers measured mRNA levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the cortex. These were all significantly reduced in treated mice compared to controls.

A candidate for early prevention

The authors concluded that arginine behaves as a disease-modifying candidate that targets Aβ aggregation rather than just symptoms, with the benefit of being orally available, relatively cheap, and already clinically used for other indications. Because Aβ pathology begins 15 to 20 years before Alzheimer’s symptoms, they see arginine as particularly suited to long-term, preventive, or early-stage use, in contrast to expensive intravenous antibodies.

“Our findings open up new possibilities for developing arginine-based strategies for neurodegenerative diseases caused by protein misfolding and aggregation,” noted Nagai. “Given its excellent safety profile and low cost, arginine could be rapidly translated to clinical trials for Alzheimer’s and potentially other related disorders.”

Literature

[1] Fujii, K., Takeuchi, T., Fujino, Y., Tanaka, N., Fujino, N., Takeda, A., … & Nagai, Y. (2025). Oral administration of arginine suppresses Aβ pathology in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochemistry International, 106082.

[2] Tanimoto, S., & Okumura, H. (2024). Why is arginine the only amino acid that inhibits polyglutamine monomers from taking on toxic conformations?. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 15(15), 2925-2935.

[3] Bloom, G. S. (2014). Amyloid-β and tau: the trigger and bullet in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. JAMA neurology, 71(4), 505-508.

[4] Liberek, K., Lewandowska, A., & Ziętkiewicz, S. (2008). Chaperones in control of protein disaggregation. The EMBO journal, 27(2), 328-335.

[5] Fernandes, L., Cardim-Pires, T. R., Foguel, D., & Palhano, F. L. (2021). Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-gallate in amyloid aggregation and neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in neuroscience, 15, 718188.

View the article at lifespan.io