In a comprehensive review, scientists discuss the various mechanisms by which chronic infections drive cellular senescence and aging [1].

Lurking in the body

People are mostly aware of acute infections, such as the common cold, COVID-19, and malaria. Science has made great strides against these kinds of infectious diseases, making them less deadly and even eradicating some of the most dangerous ones.

Chronic infections, on the other hand, continue to fly under the radar. Most people would be generally surprised to learn how many different pathogens call their body their permanent home.

Some pathogens are surprisingly prevalent [2]. 90-95% of adults worldwide have been infected at least once with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which then lingers in the body indefinitely; the prevalence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) is thought to exceed 80%; the bacterium Helicobacter pylori can be found in almost half of the population; and there are many other examples. In short, it would be safe to say that nobody is safe.

Since many chronic infections do not cause acute symptoms, conventional medicine rarely bothers treating or even diagnosing them. However, there is increasing evidence that chronic infections can be extremely harmful, including the pre-existing infections that play a role in syndromes such as “long COVID” [3].

Some of the most important aspects of aging, such as chronic inflammation and immunosenescence, might also be driven by chronic infections. Essentially, even if pathogens do not trigger acute conditions, that doesn’t mean they are harmless.

Causing senescence via multiple routes

This new review published in Immunity and Ageing seeks to address one aspect of this relationship: the ways in which chronic infections drive cellular senescence. As the introduction puts it, “while senescence is traditionally associated with aging, growing evidence reveals that chronic infections such as viral, bacterial, and protozoan parasites can serve as powerful inducers of senescence, contributing to premature aging and long-term tissue damage.”

The researchers start with viruses. “Persistent viral infections,” they note, “have been shown to promote cellular aging through mechanisms such as the induction of cell cycle arrest, accumulation of DNA damage, and sustained secretion of proinflammatory cytokines.”

For example, hepatitis C virus (HCV) upregulates several senescence markers, such as p16, p21, p27, and γ-H2AX, in hepatocytes and promotes senescence in T cells by shortening their telomeres. Hepatic senescence-associated beta galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity is increased in approximately 50% of patients with chronic HCV.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) induces senescence in fibroblasts and renal cells, increasing pro-inflammatory senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors like IL-6 and IL-8. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) promotes senescence through viral proteins like Tat, which upregulate senescence markers and disrupt mitochondrial function.

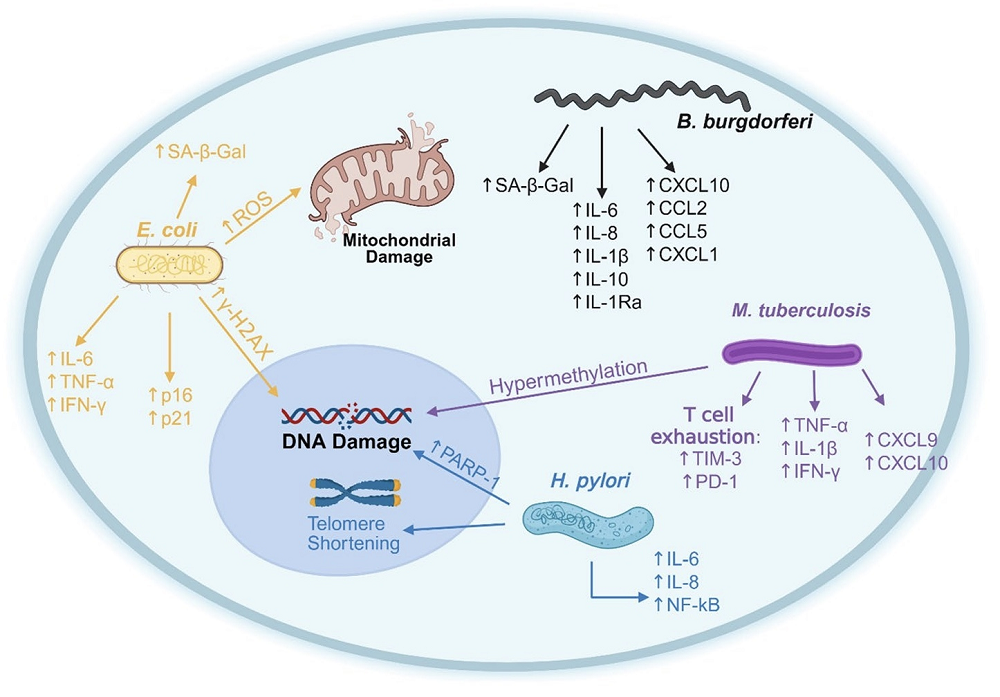

Bacterial infections can trigger cellular senescence, too. Some strains of Escherichia coli produce the toxin colibactin, which has been shown to cause senescence by inducing cell cycle arrest via DNA damage. E. coli-mediated senescence is associated with elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, which can promote tumor growth in colorectal cancer models.

Helicobacter pylori, another ubiquitous bacterium, causes telomere shortening and genomic instability through inflammation-induced oxidative stress. Here, evidence shows that senescent phenotypes persist post-eradication and extend beyond the gut. Chronic Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection results in persistent inflammation; elevated SASP proteins including TNF-α, CXCL9, and CXCL10; T-cell senescence and exhaustion; and an average increase in epigenetic age of 12-14 years.

Colonies of Borrelia burgdorferi (the parasite behind Lyme disease), the authors argue, “profoundly alter host cellular processes, causing persistent symptoms in patients and creating a physiological state reminiscent of inflammaging”, the simmering inflammation that gets stronger as we age. They cite increased levels of SA-β-gal in chronic Lyme infection, molecules found in bacterial cell walls (peptidoglycans) lingering in the liver and causing immune stimulation, and a broad inflammatory response from astrocytes in the brain triggered by B. burgdorferi’s basic membrane protein A (BmpA).

Treating chronic infections for longevity

The researchers round their review up with protozoans, single-celled eukaryotes that invade other living cells. Protozoan parasites largely follow the same “playbook.” Toxoplasma gondii causes oxidative stress, which leads to increases in the senescence markers p16 and p21, loss of the crucial structural protein Lamin B1, another hallmark of senescence, and more SASP in gut tissue.

Plasmodium infection shortens telomeres and elevates p16 and inflammatory cytokines in humans, while cerebral malaria features senescent astrocytes. Trypanosoma cruzi induces SA-β-gal, oxidative stress, DNA damage, and contractile decline in cardiomyocytes, eventually leading to cardiomyopathy in about one-third of infected patients.

This review raises important questions about the role of persistent pathogens in aging. While cellular senescence and inflammaging have multiple causes, chronic infections might be the most overlooked among them. Many chronic infections can be cured or at least reigned in with antibiotics. Doing so might slow aging, although this demands further investigation.

Literature

[1] Johnson, A., Rought, T., Aronov, J., Pokharel, P., Chiu, A., & Nasuhidehnavi, A. (2025). The impacts of chronic infections on shaping cellular senescence. Immunity & Ageing, 22(1), 37.

[2] Naghavi, M., Mestrovic, T., Gray, A., Hayoon, A. G., Swetschinski, L. R., Aguilar, G. R., … & Murray, C. J. (2024). Global burden associated with 85 pathogens in 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 24(8), 868-895.

[3] Peluso, M. J., Deveau, T. M., Munter, S. E., Ryder, D., Buck, A., Beck-Engeser, G., … & Henrich, T. J. (2023). Chronic viral coinfections differentially affect the likelihood of developing long COVID. The Journal of clinical investigation, 133(3).

View the article at lifespan.io