A new observational study suggests that men need more than twice as much exercise as women do to achieve the same level of reduction in the risk of cardiovascular heart disease [1].

Understanding sex differences

In recent years, scientists have questioned how much exercise is needed for tangible health benefits. Current guidelines from the American Heart Association, the European Society of Cardiology, and the World Health Organization suggest that everyone should be getting at least 150 minutes per week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) to significantly lower the risk of cardiovascular heart disease (CHD).

Numerous studies have added layers of complexity to these assessments, such as by showing diminishing returns, with the “sweet spot” lying around 7,000 daily steps [2] or even a U-shaped relationship, in which too much exercise can actually be harmful [3]. On many of the questions, the jury is still out.

One important piece of the puzzle, however, remains understudied: the effects of sexual differences on physical activity. Work in animal models, demographic studies, and human studies all point to the two sexes experiencing aging and disease differently. Yet, this difference is rarely accounted for in health recommendations. In this new study, scientists used data from UK Biobank (UKB), a repository of health information on about half a million British citizens, to shed some light on this question.

Men need to work twice as hard

Over 80,000 UKB participants wore wrist accelerometers for one week to record their physical activity. This created a trove of data that many scientists have used. The sample included 5,169 people with CHD at baseline and 3,764 incident CHD events with a median follow-up of about 8 years.

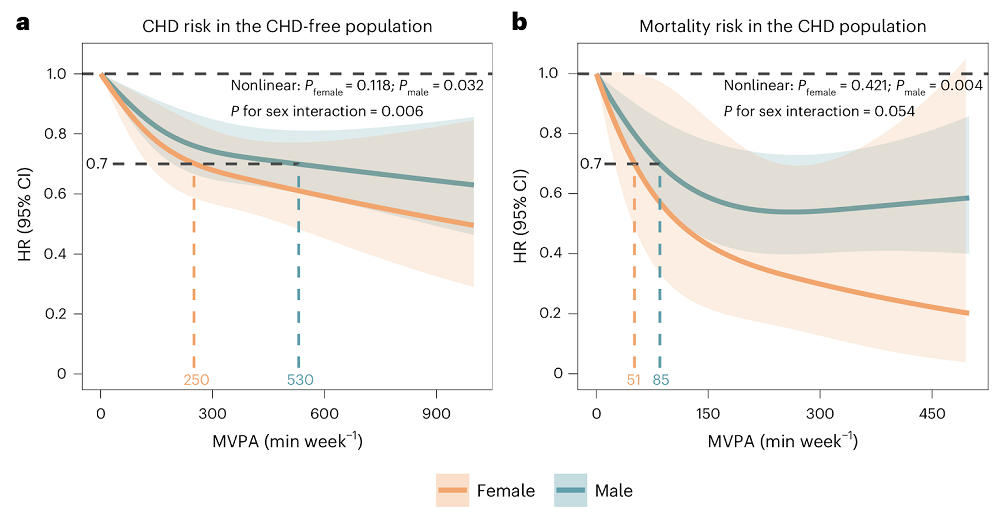

The study’s central finding was that, while women showed less adherence to the guidelines (150 minutes or above), it was also much easier for them to reach an equal reduction in CHD risk. For a 30% risk reduction, women needed about 250 min/week of MVPA, while men needed about 530 min/week: more than twice as much.

Among patients with CHD, physically active females experienced much greater mortality risk reduction than males (70% vs. only 19% in men). However, this finding, impressive as it is, was based on a far smaller CHD mortality sample (6 deaths among 340 adherent women), so estimates are imprecise even if statistically significant. The researchers urge caution and call for validation in larger CHD cohorts with wearable data.

The research went to great lengths to control for possible confounding factors. These included age, geography (England, Scotland, or Wales), ethnicity, education, Townsend deprivation index, BMI, smoking and alcohol consumption status (never/ever/current), sleep duration, a dietary health score, as well as such medical conditions and treatments as diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, use of cholesterol-lowering drugs, blood-pressure medication, insulin therapy, and Charlson comorbidity index.

The researchers also controlled for actual physical activity intensity inside the relatively wide MVPA range by measuring average acceleration. Other important variables taken into account were the polygenic risk score for CHD in incidence models and CHD treatment medications (antiplatelet, antianginal) in the mortality models. People who are already sick are likely to undergo less physical activity, but this reverse causality was mitigated by excluding participants who had events that occurred in the first year after accelerometer wear.

The team ran multiple model specifications with different covariate sets to confirm that the sex-interaction findings were not model-dependent. This did not fundamentally change the results: women benefited more per unit of MVPA across all these specifications, time scales, and strategies.

Possible explanations

The authors also hypothesized possible biological underpinnings of their results. For instance, higher circulating estrogen in women can shift fuel use toward greater lipid oxidation during exercise, which is linked to better CHD outcomes. Sex differences in fiber-type composition (women have more type I fibers, while men have more type II) and oxidative capacity could make women more “PA-sensitive,” yielding larger clinical benefit per minute.

The study’s observational design means that it cannot establish causality, only correlation, and causality and mechanisms will have to be elucidated by future research. Still, the pattern is consistent with prior accelerometer studies in older women [4].

The take-home message is important both for men and women. Since adherence is generally lower in women, knowing that they need much less effort to achieve the same CHD risk reduction may be encouraging. On the other hand, men should know that adhering to the current “sex-blind” guidelines might not be enough.

Literature

[1] Chen, J., Wang, Y., Zhong, Z., Chen, X., Zhang, L., Jie, L., … & Wang, Y. (2025). Sex differences in the association of wearable accelerometer-derived physical activity with coronary heart disease incidence and mortality. Nature Cardiovascular Research, 1-11.

[2] ing, D., Nguyen, B., Nau, T., Luo, M., del Pozo Cruz, B., Dempsey, P. C., … Owen, K. (n.d.). Daily steps and health outcomes in adults: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health.

[3] Schnohr, P., O’Keefe, J. H., Marott, J. L., Lange, P., & Jensen, G. B. (2015). Dose of jogging and long-term mortality: the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 65(5), 411-419.

[4] LaMonte, M. J., Buchner, D. M., Rillamas‐Sun, E., Di, C., Evenson, K. R., Bellettiere, J., … & LaCroix, A. Z. (2018). Accelerometer‐measured physical activity and mortality in women aged 63 to 99. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(5), 886-894.

View the article at lifespan.io