In Aging Cell, researchers have described how an age-related deficiency in another compound leads the antioxidant FoxO1 to contribute to bone deterioration in osteoporosis by siphoning from a bone-building pathway.

A harmful antioxidant?

Because they fight against harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS), antioxidants, both external and internal, are normally viewed as having positive effects against aging. This includes bone tissue, as previous work has found that knocking out FoxO1 harms bone formation while inducing its overexpression leads to more bone building [1].

On the other hand, another team of researchers has found that knocking out FoxO1 in osteoblasts, the cells responsible for building bone, can lead to greater bone formation rather than any depletion [2]. Those researchers discovered some of the reasons why, finding that FoxO1 can have a negative effect on the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in older animals [3].

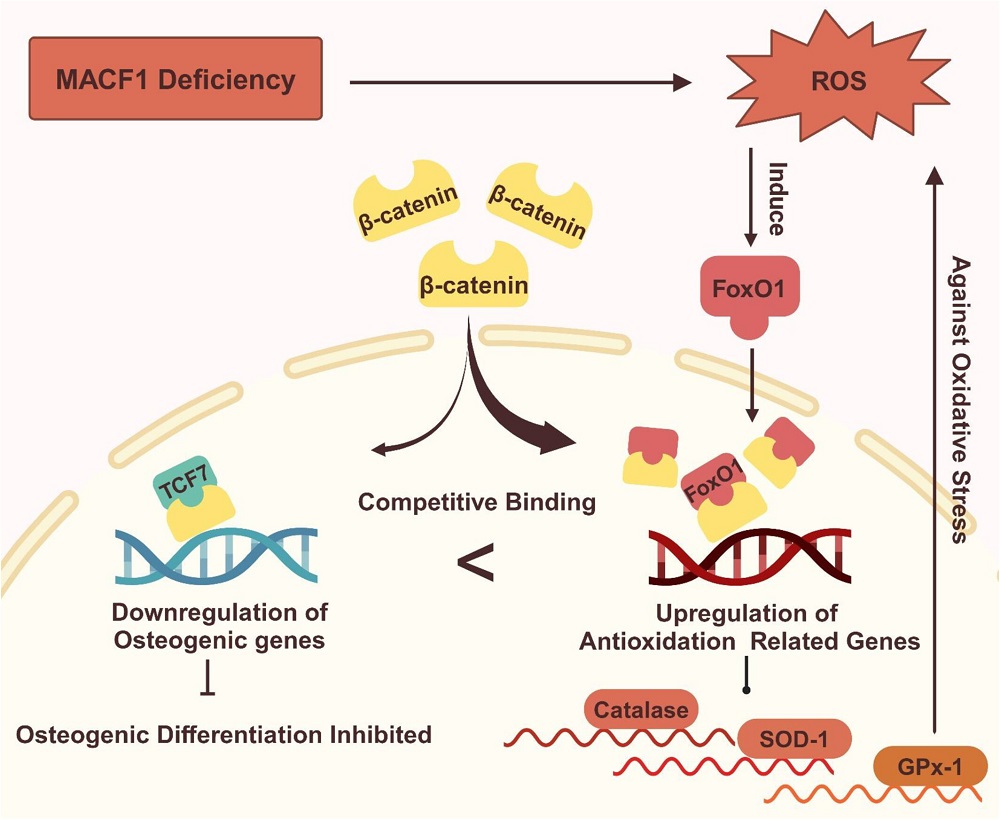

This paper builds upon that research, focusing on MACF1, a protein that diminishes with age and has been pinpointed as playing a key role in osteoporosis. Unsurprisingly, it too plays a crucial role in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway that osteoblasts need to function [4]. These researchers, therefore, decided to investigate the relationship between FoxO1 and MACF1 in this context.

MACF1 knockout leads to oxidative stress

The researchers took populations of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), some of which had MACF1 knocked out, and exposed them to hydrogen peroxide, a strong oxidant. Runx2 and Alp, two factors necessary for the differentiation and function of osteoblasts, were significantly reduced by both MACF1 knockout and by oxidative stress. While either MACF1 knockout or oxidative stress had measurable negative effects on mineralization, mineralization loss was especially profound in the MACF1-knockout cells exposed to the peroxide. Overall, this experiment led the researchers to hold that “the absence of MACF1 in cells results in persistent and high levels of ROS, leading to chronic oxidative stress and inhibiting the differentiation of osteoblastic cells.”

A further experiment on mice found that oxidative stress was indeed a key link in this relationship. Untreated, mice with MACF1 knocked out experience significantly greater frailty and live significantly shorter lives than unmodified mice, having a 50% mortality rate at only 19 months of age. Treatment with the antioxidant NAC increased this survival rate to 100%, the same as wild-type mice, and restored some of the frailty markers.

Too focused on survival to differentiate

The researchers then turned to the main thrust of their paper, linking MACF1, β-catenin, and FoxO1. They found that exposing cells to hydrogen peroxide significantly reduced β-catenin, but supplying them with NAC did not affect it. MACF1-knockout cells always had elevated levels of FoxO1, whether or not they were exposed to hydrogen peroxide. A fluorescence measurement found that treatment with NAC reduced the intensity of FoxO1.

Most crucially, the researchers found that FoxO1 “seizes” β-catenin away from TCF7, a crucial compound in osteoblast differentiation. This altered the cells’ fate; instead of properly differentiating into osteoblasts, the affected cells were focused on fighting their own oxidation. The MACF1 knockdown spurred this transition, causing FoxO1 and β-catenin to co-locate in greater amounts than in unmodified cells. Treatment with NAC partially alleviated this condition.

This research pinpoints MACF1 as a key target in future work, particularly since it dovetails with other research showing that MACF1 plays a key function in the stability of other cells, including neurons [5]. While treatment with antioxidants, which reduces the need for FoxO1, appears to be beneficial in allowing osteoblasts to properly differentiate, restoring the levels of MACF1, a key compound that decreases with age, appears to be necessary. Further work will have to be done to determine how this may be accomplished.

Literature

[1] Rached, M. T., Kode, A., Xu, L., Yoshikawa, Y., Paik, J. H., DePinho, R. A., & Kousteni, S. (2010). FoxO1 is a positive regulator of bone formation by favoring protein synthesis and resistance to oxidative stress in osteoblasts. Cell metabolism, 11(2), 147-160.

[2] Xiong, Y., Zhang, Y., Guo, Y., Yuan, Y., Guo, Q., Gong, P., & Wu, Y. (2017). 1α, 25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 increases implant osseointegration in diabetic mice partly through FoxO1 inactivation in osteoblasts. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 494(3-4), 626-633.

[3] Xiong, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhou, F., Liu, Y., Yi, Z., Gong, P., & Wu, Y. (2022). FOXO1 differentially regulates bone formation in young and aged mice. Cellular Signalling, 99, 110438.

[4] Yin, C., Tian, Y., Hu, L., Yu, Y., Wu, Z., Zhang, Y., … & Qian, A. (2021). MACF1 alleviates aging‐related osteoporosis via HES1. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine, 25(13), 6242-6257.

[5] Okenve-Ramos, P., Gosling, R., Chojnowska-Monga, M., Gupta, K., Shields, S., Alhadyian, H., … & Sanchez-Soriano, N. (2024). Neuronal ageing is promoted by the decay of the microtubule cytoskeleton. PLoS biology, 22(3), e3002504.

View the article at lifespan.io