A recent review of literature investigated the risks and benefits of hormone replacement therapy. The authors point out that this approach could be used as a geroprotector to extend the healthspan of women. However, the risk-benefit ratio should be individually evaluated. [1]

Sex-specific aging trajectories

Female and male aging trajectories differ, and one contributor is sex-specific hormones and reproductive organ aging. We have discussed this in detail in two pieces dedicated to female reproductive aging and menopause, but in brief, the decline in female reproduction, specifically the decrease in estrogen and progesterone production, occurs relatively early in life, accelerating many aging processes.

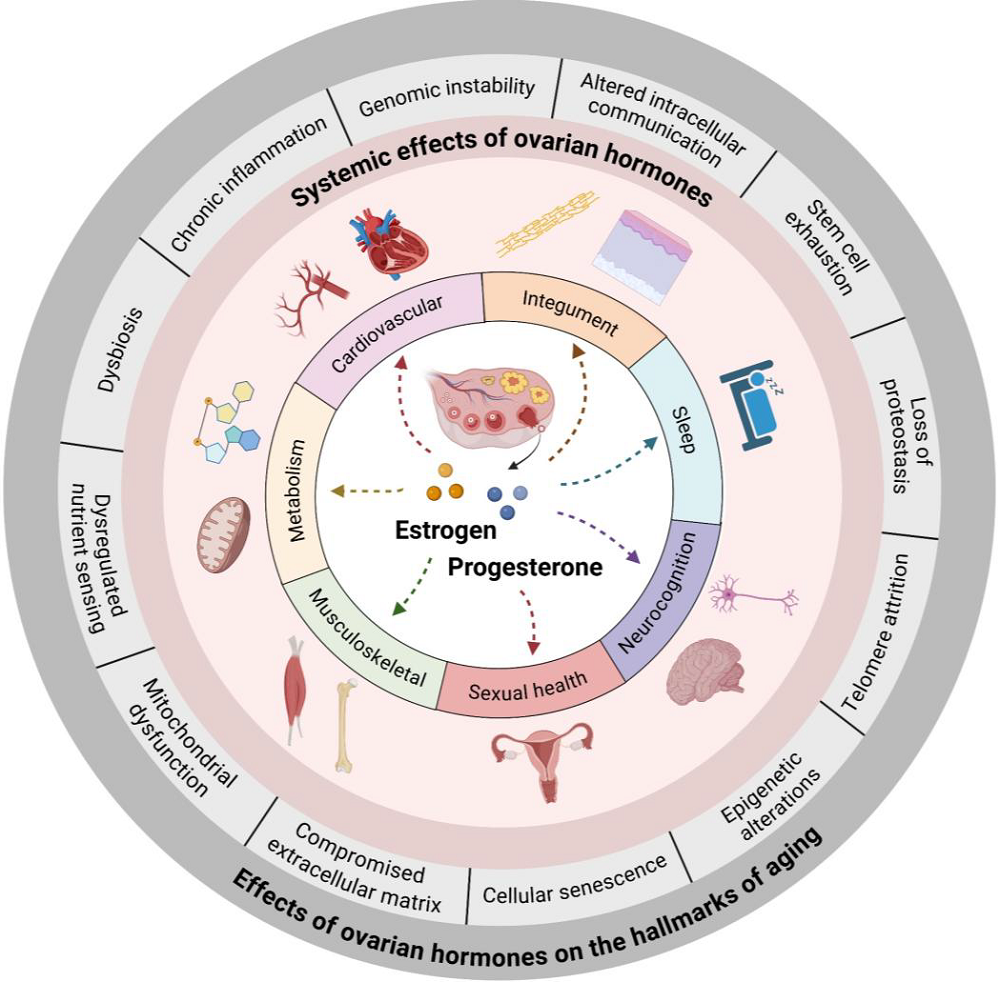

The roles of estrogens and progesterone are not limited to reproductive organs; they affect the whole body’s health. Therefore, their withdrawal leads to numerous disturbances and negative consequences, such as a higher risk of osteoporosis, sarcopenia, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and cognitive impairment along with many unpleasant everyday symptoms such as hot flashes and sleep disturbances [2].

More than managing symptoms

To remedy the loss of hormones associated with menopausal transition and address associated symptoms, women might be prescribed hormone replacement therapy. Currently, clinical practice uses this treatment for symptomatic menopausal patients. However, the authors of this review present evidence that it could be used as a “continued proactive geroprotective strategy in healthy, mid-life women, independent of ongoing symptom status.” In this light, hormone replacement therapy can be used as an intervention to slow or reverse biological aging processes.

This is supported by the molecular roles of estrogen and progesterone, which affect different “hallmarks of aging,” suggesting that hormone replacement can help mitigate the negative impact of estrogen and progesterone withdrawal on those hallmarks.

Estrogen has been described to have geroprotective effects across the 12 hallmarks of aging. Broadly speaking, estrogen was shown to “enhance genomic stability, support telomere maintenance, modulate epigenetic patterns, and promote mitochondrial efficiency, preserve proteostasis, suppress chronic inflammation, and maintain intercellular communication and extracellular matrix integrity.” Progesterone also has ben shown to have many positive effects on cellular processes, including “modulating autophagy, maintaining general hormonal and immune balance, and supporting tissue regeneration and stem cell homeostasis.” Therefore, they can work in concert to preserve health.

Weighing risks and benefits

Going beyond first-order molecular interactions, hormone replacement therapy has also been shown to have geroprotective effects on many systems, including improving cardiovascular health by reducing progression of atherosclerosis and coronary events [3]; reducing postmenopausal osteoporosis by reducing vertebral and hip fractures by around 34% [4]; improving sleep quality; improving different metrics of memory and visuospatial skills [5]; and improving metabolic health by counteracting various aging-related metabolic changes, such as increased adiposity and insulin resistance [6]. It was also reported to improve sexual function and improve overall quality of life [7].

Those reported beneficial effects suggest that there is a need to change current clinical guidance and include women who do not experience menopause-related symptoms as potential candidates for hormone replacement therapy.

That said, the authors recognize that this approach has been associated with some adverse effects. For example, it was shown to increase the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), especially when taken as oral estrogen preparations. The risk of stroke and coronary events can also increase if hormone replacement is initiated more than 10 years after menopause [8].

Timing appears to be a crucial factor here, and its importance is underscored by a recent subgroup analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) data and findings from the ELITE trial, which suggest that initiating hormone replacement therapy within 10 years of menopause or before age 60 decreases its risks and may lead to greater cardiovascular benefits [9].

The route of administration is also essential. Studies have found that transdermal estrogen formulations and micronized progesterone are safer when it comes to VTE, stroke, breast cancer, and metabolic effects [10, 11].

There are also other factors that are important in personalizing such a therapy, including whether the patient had a hysterectomy or still has a uterus; in the former case, estrogen-only therapy is better, and in the latter, combined estrogen/progesterone is recommended [12], with micronized progesterone appearing to be a safer option in general.

Personalizing the approach

The authors propose dividing women into three groups based on risk-benefit ratio:

- The low-risk group consists of women who can be considered for early hormone replacement therapy. Women in this group are below the age of 60, have experienced less than 10 years since menopause, have a BMI lower than 30, no cardiovascular diseases, and do not smoke.

- The intermediate-risk group consists of women who may be considered for a personalized approach and should be monitored during use. They might have mild metabolic syndrome, a family history of cardiovascular diseases, or a history of smoking.

- The high-risk group should avoid hormone replacement therapy. Those are patients with prior VTE, stroke, active malignancies, or uncontrolled cardiovascular diseases.

However, this general framework could be further personalized by evaluating aging-related biomarkers. The authors propose including epigenetic clocks, inflammatory biomarkers since chronic low-grade inflammation frequently increases during the menopausal transition, metabolic markers, cardiovascular aging metrics, bone turnover biomarkers, neurocognitive and sleep biomarkers, and ovarian aging markers. While those biomarkers can provide a lot of information, they also have limitations. It is also recommended to integrate information from multiple biomarkers rather than relying on a single one.

The authors also suggest conducting larger future trials to continue evaluating different trajectories and personalized approaches, as well as the possibility of combining hormone replacement with other geroprotective therapies.

Literature

[1] Rabinovici, J., Oonk, H. P., Huang, Z., Mirando, T., Zhou, M., Strauss, T., Olari, L. R., Wilczok, D., Maier, A. B., & Bischof, E. (2025). Perimenopausal Hormone Replacement Treatments as a Geroprotective Approach – Adapting Clinical Guidance. Aging and disease, 10.14336/AD.2025.1391. Advance online publication.

[2] Dong, L., Teh, D. B. L., Kennedy, B. K., & Huang, Z. (2023). Unraveling female reproductive senescence to enhance healthy longevity. Cell research, 33(1), 11–29.

[3] Hodis, H. N., & Mack, W. J. (2014). Hormone replacement therapy and the association with coronary heart disease and overall mortality: clinical application of the timing hypothesis. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology, 142, 68–75.

[4] Mosekilde, L., Beck-Nielsen, H., Sørensen, O. H., Nielsen, S. P., Charles, P., Vestergaard, P., Hermann, A. P., Gram, J., Hansen, T. B., Abrahamsen, B., Ebbesen, E. N., Stilgren, L., Jensen, L. B., Brot, C., Hansen, B., Tofteng, C. L., Eiken, P., & Kolthoff, N. (2000). Hormonal replacement therapy reduces forearm fracture incidence in recent postmenopausal women – results of the Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study. Maturitas, 36(3), 181–193.

[5] Santoro N. (2025). Understanding the menopause journey. Climacteric : the journal of the International Menopause Society, 28(4), 384–388.

[6] Nejat, E. J., Polotsky, A. J., & Pal, L. (2010). Predictors of chronic disease at midlife and beyond–the health risks of obesity. Maturitas, 65(2), 106–111.

[7] Portman, D. J., Gass, M. L., & Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel (2014). Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Menopause (New York, N.Y.), 21(10), 1063–1068.

[8] Canonico, M., Plu-Bureau, G., Lowe, G. D., & Scarabin, P. Y. (2008). Hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 336(7655), 1227–1231.

[9] Hodis, H. N., Mack, W. J., Henderson, V. W., Shoupe, D., Budoff, M. J., Hwang-Levine, J., Li, Y., Feng, M., Dustin, L., Kono, N., Stanczyk, F. Z., Selzer, R. H., Azen, S. P., & ELITE Research Group (2016). Vascular Effects of Early versus Late Postmenopausal Treatment with Estradiol. The New England journal of medicine, 374(13), 1221–1231.

[10] Scarabin, P. Y., Oger, E., Plu-Bureau, G., & EStrogen and THromboEmbolism Risk Study Group (2003). Differential association of oral and transdermal oestrogen-replacement therapy with venous thromboembolism risk. Lancet (London, England), 362(9382), 428–432.

[11] Fournier, A., Berrino, F., Riboli, E., Avenel, V., & Clavel-Chapelon, F. (2005). Breast cancer risk in relation to different types of hormone replacement therapy in the E3N-EPIC cohort. International journal of cancer, 114(3), 448–454.

[12] Academic Committee of the Korean Society of Menopause, Lee, S. R., Cho, M. K., Cho, Y. J., Chun, S., Hong, S. H., Hwang, K. R., Jeon, G. H., Joo, J. K., Kim, S. K., Lee, D. O., Lee, D. Y., Lee, E. S., Song, J. Y., Yi, K. W., Yun, B. H., Shin, J. H., Chae, H. D., & Kim, T. (2020). The 2020 Menopausal Hormone Therapy Guidelines. Journal of menopausal medicine, 26(2), 69–98.

View the article at lifespan.io