In Aging Cell, four Japanese researchers have recently described the aging of the hematopoietic system, which is responsible for the creation of blood.

A system that affects all the others

Aging and age-related diseases are often discussed in terms of hallmarks, such as senescence and genomic instability. However, the bodies of complex organisms, such as humans, have systems that are all affected differently by these hallmarks, and many of them have downstream consequences for the rest of the body.

These researchers note that hematopoietic aging appears to be driven by metabolic issues, epigenetic alterations, genomic instability, and inflammaging, although they contend that inflammaging may have more roots in environmental factors than intrinsic ones [1].

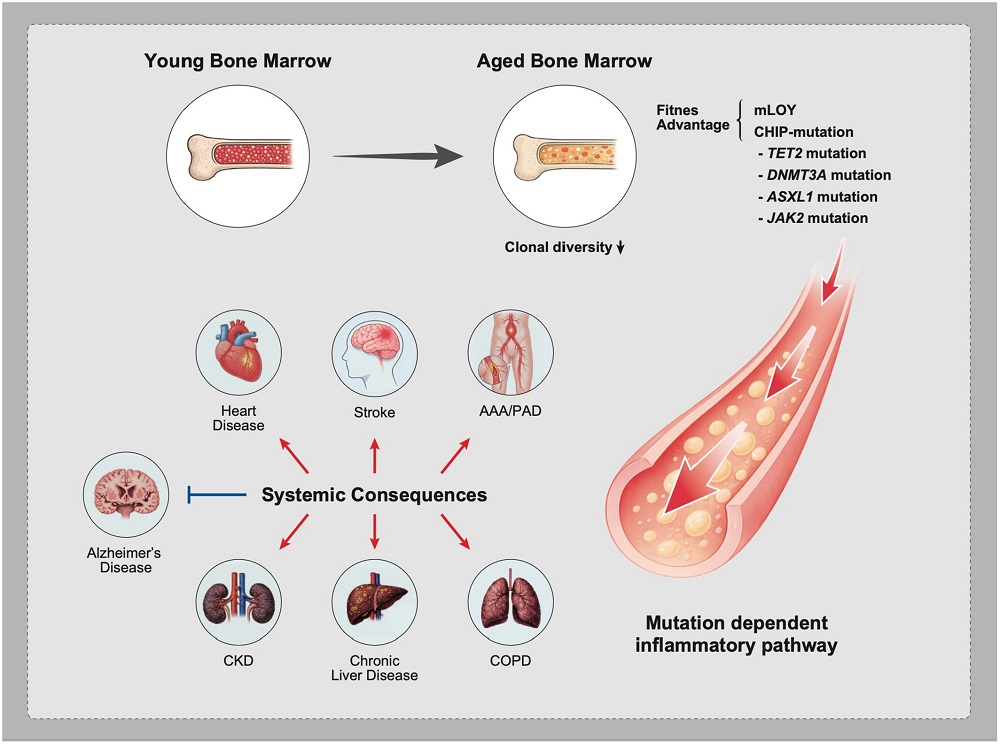

Being responsible for the creation of blood, this particular aging leads to severe consequences. One major aspect of this system’s aging is clonal hematopoiesis, which generates a steady population of mutant cells that have evolved more towards parasitism than fulfilling the body’s needs; this is directly linked to multiple age-related diseases, such as atherosclerosis [2], and as can be expected, aging of the blood system is linked to the aging of many other organs.

This review, therefore, aims to summarize the current state of knowledge about hematopoietic aging an what might be done about it.

Fundamental causes

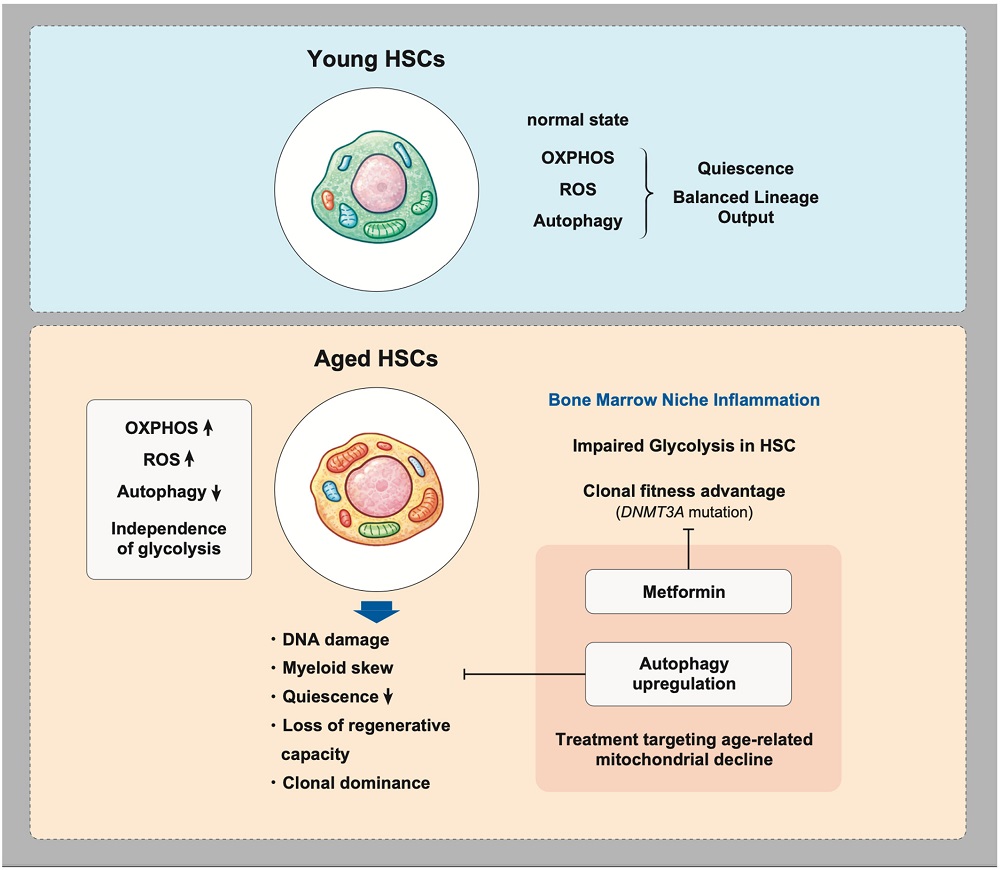

DNA aging caused by oxidative stress has been found to be a key part of hematopoietic aging; fortunately, this appears to be potentially mitigated through antioxidants [3]. Mitochondrial dysfunction, another hallmark of aging, spurs this oxidative stress [4], and this is exacerbated by a reduction in the cellular maintenance process known as autophagy, which destroys defective mitochondria and other unwanted organelles [5].

This DNA damage is key to the beginnings of clonal hematopoiesis. Three epigenetic regulator genes, DNMT3A, TET2, and ASXL1, have been identified as conferring advantages to these mutants over more functional cells. Broader changes such as mosaic mutations can also occur, and in men, the Y chromosomes of these cells may be entirely absent with advanced age, making them more susceptible to age-related diseases [6].

The mutant cells are better adapted to survive in an inflammatory environment than regular cells are. They have less mitochondrial maintenance, but their mitochondria are more active, and they have abandoned function in favor of proliferation. While they are still technically stem cells, they behave somewhat more like cancer. Metformin has been reported to mitigate the advantages that these clones have, preventing them from excessively proliferating [7]. Other cells upregulate mitochondrial activity while still maintaining their function, and those cells have been suggested as being useful for therapies [8].

When the marrow promotes aging

Among the characteristics of aged bone marrow, the reviewers found that three stand out in particular: a reduction in the number of blood vessels [9], an increase in fat [10], and the depletion of osteoblasts [11], which are responsible for building bone. Not all bones suffer the same amount of this dysregulation; the femur ages rapidly, but the skull is less vulnerable, and its bone marrow remains robust throughout life [12].

Physical stresses have been reported to be a key part of these negative effects. As the extracellular matrix stiffens, the bone marrow stem cell niche is degraded [13]. Likewise, an increase in fat might be both a cause and consequence of altered hematopoiesis [14]. The contributions of inflammation in the microenvironment are unsurprising, with even short bursts of inflammation leading to long-lasting consequences [15]. This inflammation can come from multiple sources, including the gut flora [16]; while gut-related therapies have been found to work in mice [17], it is uncertain if they can work in people.

Potential therapies

Other than the potential interventions already discussed, the reviewers suggest other strategies for abating this problem. Cellular senescence is one obvious target, as senescent cells leak factors that promote systemic inflammation; however, while senolytics and senomorphics that target these cells have been found to have broad benefits, the researchers note that their effects in this particular context are unclear.

Youthful plasma transfusion appears to be effective in some contexts, such as for bone marrow stromal cells [18], although it may or may not directly affect hematopoietic decline. The reviewers suggest that therapies directly targeted at the hematopoietic niche, such as directly targeting clones, may be more effective. Future work will need to be done to determine the approaches that can halt or reverse clonal hematopoiesis and related problems.

Literature

[1] Franck, M., Tanner, K. T., Tennyson, R. L., Daunizeau, C., Ferrucci, L., Bandinelli, S., … & Cohen, A. A. (2025). Nonuniversality of inflammaging across human populations. Nature aging, 1-10.

[2] Jaiswal, S., Natarajan, P., Silver, A. J., Gibson, C. J., Bick, A. G., Shvartz, E., … & Ebert, B. L. (2017). Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 377(2), 111-121.

[3] Yahata, T., Takanashi, T., Muguruma, Y., Ibrahim, A. A., Matsuzawa, H., Uno, T., … & Ando, K. (2011). Accumulation of oxidative DNA damage restricts the self-renewal capacity of human hematopoietic stem cells. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology, 118(11), 2941-2950.

[4] Bratic, A., & Larsson, N. G. (2013). The role of mitochondria in aging. The Journal of clinical investigation, 123(3), 951-957.

[5] Warr, M. R., Binnewies, M., Flach, J., Reynaud, D., Garg, T., Malhotra, R., … & Passegué, E. (2013). FOXO3A directs a protective autophagy program in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature, 494(7437), 323-327.

[6] Bruhn-Olszewska, B., Markljung, E., Rychlicka-Buniowska, E., Sarkisyan, D., Filipowicz, N., & Dumanski, J. P. (2025). The effects of loss of Y chromosome on male health. Nature Reviews Genetics, 26(5), 320-335.

[7] Hosseini, M., Voisin, V., Chegini, A., Varesi, A., Cathelin, S., Ayyathan, D. M., … & Chan, S. M. (2025). Metformin reduces the competitive advantage of Dnmt3a R878H HSPCs. Nature, 1-10.

[8] Totani, H., Matsumura, T., Yokomori, R., Umemoto, T., Takihara, Y., Yang, C., … & Suda, T. (2025). Mitochondria-enriched hematopoietic stem cells exhibit elevated self-renewal capabilities, thriving within the context of aged bone marrow. Nature Aging, 1-17.

[9] Stucker, S., Chen, J., Watt, F. E., & Kusumbe, A. P. (2020). Bone angiogenesis and vascular niche remodeling in stress, aging, and diseases. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology, 8, 602269.

[10] Ambrosi, T. H., Scialdone, A., Graja, A., Gohlke, S., Jank, A. M., Bocian, C., … & Schulz, T. J. (2017). Adipocyte accumulation in the bone marrow during obesity and aging impairs stem cell-based hematopoietic and bone regeneration. Cell stem cell, 20(6), 771-784.

[11] Morrison, S. J., & Scadden, D. T. (2014). The bone marrow niche for haematopoietic stem cells. Nature, 505(7483), 327-334.

[12] Koh, B. I., Mohanakrishnan, V., Jeong, H. W., Park, H., Kruse, K., Choi, Y. J., … & Adams, R. H. (2024). Adult skull bone marrow is an expanding and resilient haematopoietic reservoir. Nature, 636(8041), 172-181.

[13] Zhang, X., Cao, D., Xu, L., Xu, Y., Gao, Z., Pan, Y., … & Yue, R. (2023). Harnessing matrix stiffness to engineer a bone marrow niche for hematopoietic stem cell rejuvenation. Cell stem cell, 30(4), 378-395.

[14] Tuljapurkar, S. R., McGuire, T. R., Brusnahan, S. K., Jackson, J. D., Garvin, K. L., Kessinger, M. A., … & Sharp, J. G. (2011). Changes in human bone marrow fat content associated with changes in hematopoietic stem cell numbers and cytokine levels with aging. Journal of anatomy, 219(5), 574-581.

[15] Bogeska, R., Mikecin, A. M., Kaschutnig, P., Fawaz, M., Büchler-Schäff, M., Le, D., … & Milsom, M. D. (2022). Inflammatory exposure drives long-lived impairment of hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal activity and accelerated aging. Cell stem cell, 29(8), 1273-1284.

[16] Agarwal, P., Sampson, A., Hueneman, K., Choi, K., Jakobsen, N. A., Uible, E., … & Starczynowski, D. T. (2025). Microbial metabolite drives ageing-related clonal haematopoiesis via ALPK1. Nature, 1-11.

[17] Zeng, X., Li, X., Li, X., Wei, C., Shi, C., Hu, K., … & Qian, P. (2023). Fecal microbiota transplantation from young mice rejuvenates aged hematopoietic stem cells by suppressing inflammation. Blood, 141(14), 1691-1707.

[18] Baht, G. S., Silkstone, D., Vi, L., Nadesan, P., Amani, Y., Whetstone, H., … & Alman, B. A. (2015). Exposure to a youthful circulation rejuvenates bone repair through modulation of β-catenin. Nature communications, 6(1), 7131.

View the article at lifespan.io