A recent study suggests that cognitive enrichment throughout life is associated with reduced dementia risk, and it has the potential to delay the onset of dementia and mild cognitive impairment by five to seven years [1].

Cognitive stimulation

Engagement in cognitively stimulating activities has been linked to lower dementia incidence, better cognitive function, and a slower rate of cognitive decline [2-4]. However, previous studies have some limitations. First, they often examine engagement in cognitive activities at a single life stage. Second, they frequently focus on a single activity, such as solving crossword puzzles.

While it’s important to identify which activities and at what life stages contribute to maintaining cognitive function in older age, it’s also essential to recognize that these activities are part of broader lifestyles that individuals engage in throughout their lives, collectively affecting cognition.

To gain a more comprehensive picture, the current study examined the relationships between lifetime cognitive enrichment, access to various resources throughout life, Alzheimer’s disease-related dementia, and cognitive decline.

Measuring cognitive enrichment

This longitudinal study examined 1,939 older adults with a mean baseline age of 80 years, mostly female, from Northeastern Illinois who participated in the Rush Memory and Aging Project. The cohort consisted mostly of highly educated, non-Hispanic White people of European descent, which could limit generalizability. Participants were free of dementia at the beginning of the study and underwent annual clinical evaluations for almost 8 years. During that time, 551 persons developed Alzheimer’s disease-related dementia.

Based on lifetime-enrichment data collected through surveys, the researchers developed a composite measure of enrichment that captures each individual’s living environment.

“Our study looked at cognitive enrichment from childhood to later life, focusing on activities and resources that stimulate the mind,” said study author Andrea Zammit, Ph.D., of Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

For early-life enrichment, the researchers took into account such factors as parental education; number of siblings; access to various cognitive resources at age 12, such as a newspaper subscription, encyclopedia, globe, or atlas; frequency of cognitively stimulating activities at age 6, for example, being read to; similar activities at age 12, such as reading books; and foreign language instruction before age 18.

For midlife and late life, the researchers considered income and frequency of engagement in cognitive activities; additionally, at the midlife time point, they assessed access to cognitive resources such as magazines, a dictionary, or a library card.

A lifetime enrichment composite score was computed as the average of the three composite scores and was moderately correlated with education and global cognition.

Higher enrichment, lower dementia risk

The analysis of the data showed that every point higher in lifetime enrichment was associated with a 38% reduced risk of dementia and a 36% reduced risk of mild cognitive impairment.

When scores were analyzed separately, the benefits of cognitive enrichment were evident as well, with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease-related dementia reduced by 20%, 21%, and 29%, and the risk of cognitive impairment lower by 17%, 20%, and 24% for early-, mid-, and late-life cognitive enrichment, respectively.

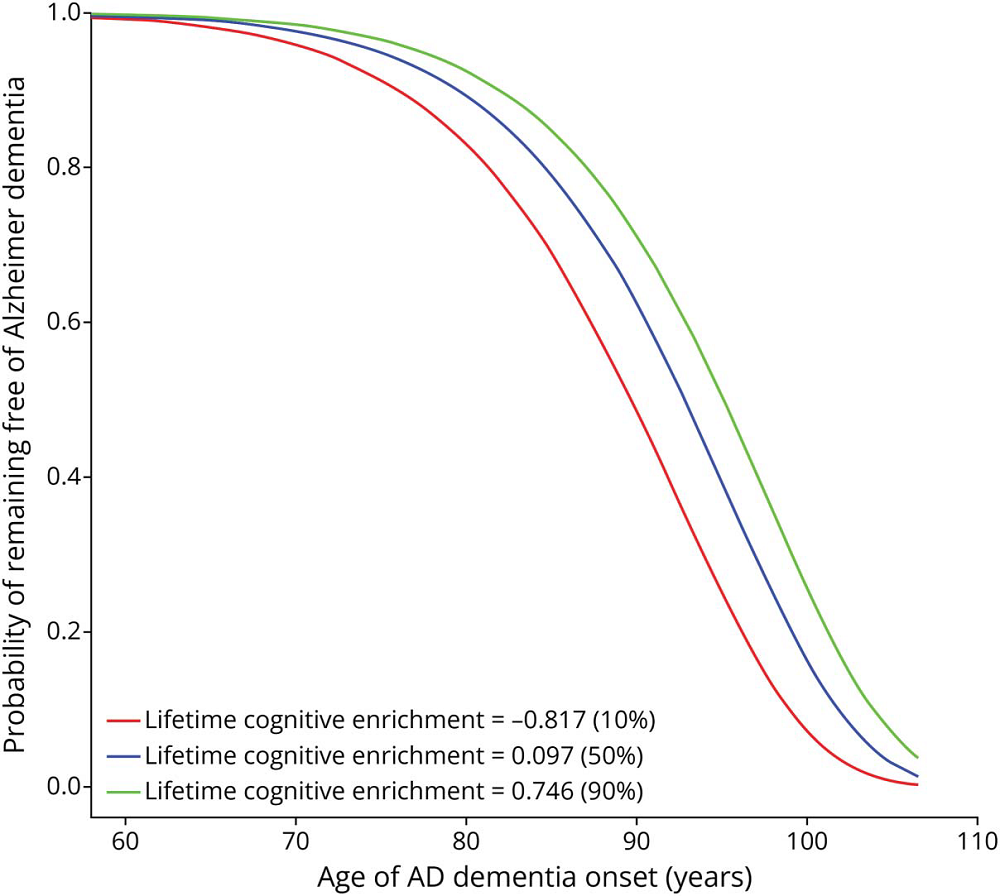

The researchers also calculated that for people at the 90th percentile of lifetime cognitive enrichment, compared with people at the 10th percentile, dementia onset was delayed by almost 5.5 years, with a mean age of 93.8 years (compared to 88.4 years); and for mild cognitive impairment by 7 years, with a mean age of 84.5 years (compared to 77.5 years). The delay was also present when each stage was analyzed separately, but it was smaller for early and mid-life enrichment.

The authors noted differences among study participants at baseline that they attributed to lifetime cognitive enrichment. The cognitive abilities of people at the 10th percentile declined 14% faster than those at the 50th percentile, and those at the 90th percentile declined 10% more slowly.

Among people who died during the follow-up period, the researchers didn’t observe meaningful associations between cognitive enrichment scores and neuropathological changes in the brain. However, they observed associations between higher cognitive enrichment scores and better cognitive function near death and slower cognitive decline.

Individual factors

While composite scores of cognitive enrichment are important for showing global trends, the researchers also conducted separate analyses of individual indicators, which showed a positive association with late-life cognition for all tested indicators except the availability of childhood resources.

The greatest effects were observed for midlife participation in cognitive activities and foreign language instruction, even after adjusting for socioeconomic status. It’s not the first time that learning a foreign language has appeared as a protective factor against cognitive decline or aging. We recently discussed a study linking multilingualism to delayed aging, which further supports the beneficial effects of speaking more than one language.

Lifelong consistency

The researchers conclude that “results suggest that cognitive health in late life is in part the product of lifetime exposure to cognitive enrichment,” and higher lifelong cognitive enrichment has the potential to reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease by nearly 40%. While the effect seems to be the strongest for mid- and late-life engagement, the researchers make an argument about the importance of creating intellectually stimulating environments in early life, as this helps to instill the love of lifelong learning in young individuals, which will help them to reap the benefits of intellectual engagement later in life. They also recommend public investment in creating spaces that provide free access to cognitively stimulating activities, such as libraries and other free services, so that these resources are readily available to those with limited financial resources.

“Our findings are encouraging, suggesting that consistently engaging in a variety of mentally stimulating activities throughout life may make a difference in cognition,” said Zammit. “Public investments that expand access to enriching environments, like libraries and early education programs designed to spark a lifelong love of learning, may help reduce the incidence of dementia.”

Literature

[1] Zammit, A. R., Yu, L., Poole, V. N., Kapasi, A., Wilson, R. S., & Bennett, D. A. (2026). Associations of Lifetime Cognitive Enrichment With Incident Alzheimer Disease Dementia, Cognitive Aging, and Cognitive Resilience. Neurology, 106(5), e214677.

[2] Wang, H. X., Karp, A., Winblad, B., & Fratiglioni, L. (2002). Late-life engagement in social and leisure activities is associated with a decreased risk of dementia: a longitudinal study from the Kungsholmen project. American journal of epidemiology, 155(12), 1081–1087.

[3] Gow, A. J., Pattie, A., & Deary, I. J. (2017). Lifecourse Activity Participation From Early, Mid, and Later Adulthood as Determinants of Cognitive Aging: The Lothian Birth Cohort 1921. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences, 72(1), 25–37.

[4] Stern, C., & Munn, Z. (2010). Cognitive leisure activities and their role in preventing dementia: a systematic review. International journal of evidence-based healthcare, 8(1), 2–17.

View the article at lifespan.io